Friends, it has been a longer time than I like to contemplate, but this trilogy remains one of the major priorities of my artistic life. So when my wife and I managed to take a two day getaway for my birthday over last weekend, which served as a sort of mini writers' retreat, I gratefully took the time to finish this chapter. I hope you enjoy it. It will certainly not be so long before I post another.

In Chapter 8 we return to Jozef, and we meet a cavalry regiment of the Polish Legion. They're a historically fascinating group, whose founder, Joseph Pilsudski became the father of independent Poland. But I'll let the chapter introduce them to you properly.

Klimontów, Galicia. June 28nd, 1915. It was a distance of less than thirty kilometers from Sandomierz where Jozef’s regiment was stationed -- his former regiment as the orders in his uniform pocket made clear -- to Klimontów where the 1st Cavalry Regiment of the Polish Legion was recovering from a recent engagement. There was no military train available, and Jozef was humiliatingly unable to make the journey on horseback because his mount belonged to the Uhlan regiment. So with his orders in hand and his cavalry spurs jingled on his boots, he was required to stand in line behind two old women carrying chickens in wicker baskets, show his orders to the ticket-master at the Sandomierz train station, and receive a second class ticket (the local train offered no first class) on the slow train to his destination.

The one second class carriage was comfortingly empty; his two companions were a middle aged businessman in a bowler hat, who spent the entire time reading a newspaper printed indecipherably in Slovene, and an elderly Jewish woman dressed all in black who snored softly despite the hardness of the leather-upholstered seats.

Even with the frequent stops of a local train, within two hours the train pulled into Klimontów and Jozef stepped out onto the railway platform. The town was small, consisting of little more than a single square with shop fronts and houses surrounding a fountain. A little beyond, loomed bronze domes of St. Jozefa.

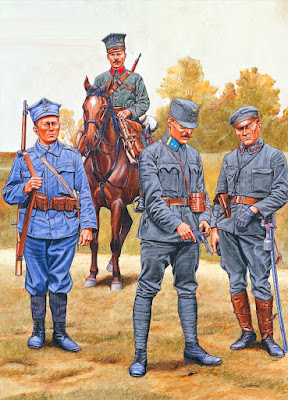

The men of the 1st Cavalry Regiment of the Legion might not outnumber the town’s residents, but they were certainly prominent. As soon as he stepped into the street Jozef saw men in field grey uniforms like his own, but with the distinctive, square-topped czapka helmet of the Polish Uhlans. Some sat at cafe tables or lounged outside shops, others walked singly or in groups. All had the casual aire of men on leave. There was no immediately obvious center of activity, no headquarters building marked out by the runners and orderlies hurrying in and out of it.

Nor did anyone immediately approach Jozef as someone out of place, even though his Austrian Uhlan’s helmet, set him apart as clearly from another regiment. After hesitating and looking about for several moments, Jozef approached a group of three men seated outside a cafe. The jumble of beer and wine glasses told that they had been at the table for some time. One had taken off his uniform tunic and rolled up the sleeves of his shirt against the heat of the day, as he sat talking with his companions and rapidly dealing out hands of some solitaire card game on the table before him.

“Where can I find the regimental headquarters?” Jozef asked, counting on the leutnant stars on his collar tabs to make clear his right to ask a peremptory question of these men whose plain collars marked them as rank and file troopers.

By rights, they should have come immediately to attention before even answering his question. They did not do this. One of the men inclined his head to the card player, as if to defer the question to him. The other fixed Jozef with a commanding eye and asked, “Which is it? Is Kandinsky a genius or an enemy of the beautiful?”

“Who?” asked Jozef.

“Oh, God!” cried the other trooper.

“I didn’t address the question of theology,” replied the first, turning on his companion. “Nor do I admit that it has any bearing on artistic expression.”

“The artistic sense is an expression of culture,” replied the second. “And culture is the expression of the people, and the organizing principle of the people is politics. Yet over politics stands the ultimate purpose of the people, and that is theology. So to the extent that art is cultural, it is political, and the end of the political is God.”

“You are drunk in the presence of an officer, and that is political,” replied the first trooper. “Sir,” he added, addressing himself to Jozef, “If you’re seeking headquarters the leutnant can help you.” He indicated the man in his shirt sleeves.

The card player ignored Jozef for a moment more as he rapidly laid down cards to complete the formation he had been creating. Then he slapped down a two of acorns with a triumphant “Aha!” and scooped up the entire deck of cards into a pile which he tapped neatly into place.

“Yes?” the card player asked. “Can I help you?”

“You are an officer, sir?” Jozef asked, with a formality that hinted skepticism.

The card player shrugged into his tunic and began buttoning it up, making his leutnant’s stars visible in the process.

“Leutnant Zelewski,” he replied, rising to his feet. “And whom do I have the pleasure to meet, sir?”

“Leutnant von Revay, 7th Imperial Royal Uhlans. I have orders to report to Oberst Gorski.”

“Well, I’d better escort you to headquarters then. Come on.”

He started down the cobbled street and Jozef fell into step next to him. The leutnant’s walk was casual, without the rigid posture most career officers had taken on through long training, and to sit drinking, his tunic off, with common troopers at a cafe would be unimaginable in a normal regiment, no matter how hot the day.

“What do you make of the tone of our regiment?” Leutnant Zelewski asked.

Jozef hesitated. The question alone suggested rather too much insight into the silent judgment he had rendered upon the regiment.

“One thing you’ll find,” Zelewski continued, “is that the backgrounds of our troopers are a little more wide ranging than the standard cut. Dudek, for instance, is a professor of political philosophy, while Bak, as perhaps you could tell, writes artistic criticism.”

“And you?” asked Jozef, wondering if all the Polish Legionnaires came from such academic backgrounds.

“Bank robber,” replied Zelewski. He let the phrase drop with conscious showmanship, and after pausing for reaction added, “And essayist. Political agitator.”

“Have you actually robbed banks?” Jozef asked, accepting the conversational bait.

“Well of course. Two banks, at any rate. And a train.”

Jozef restricted himself to a raised eyebrow.

“Banks are a tool for political control,” Zelewski explained. “And they keep a good deal of money in them as well, which comes in handy when running a revolution.”

“A revolution financed by robbing banks?”

“Well, how would you finance one?”

“I don’t know,” Jozef confessed. “Does a revolution cost much money?”

“In this present world, everything costs money. Paper and printing costs. Support for full time agitators, though with a little luck some of them have private means. Bail. A little something to help support people in exile. And then eventually arms and ammunition. With real success, a revolution is just as expensive as any other government.”

“And then you went from revolutionary bank robber to commissioned officer?”

“There are certain continuities, such as fighting the Russian tyranny. Here’s the headquarters.”

The building was, in design, a house, though the guard booth which stood next to the wrought iron gate showed that it had been some sort of official building even before the Austro-Hungarian army had taken it from the Russians. Now a Polish Legionnaire with the insignia of a gefreiter stood there, and Leutnant Zelewski nodded to him. “Is the Pulkownic available?” The non-commissioned officer promised to find out and, after saluting, hurried off towards the house. “We use Polish ranks when speaking within the Legion,” Zelewski explained. “Pulkownic is equivalent to Oberst.”

“But is that allowed? Even Hungarian units use the official rank names in German.”

“Well… Allowed. Such a strong word, don’t you think? Hardly a friendly way for allies to talk. Has anyone told you the nature of the Legion?”

“Of course.” There was something just a bit superior in Zelewski’s manner, and whether they could be friends might rely on whether he could be made to drop it. Bank robbing or no, he did not look like he was older or more experienced than Jozef himself.

“Oh? What did they tell you?”

“I was at the horse requisitions with Rittmeister Korzeniowski. He told me that the Legion was raised from among Polish patriots by the… well, by a nationalist committee of some sort. And that its leaders hope the Legion will become a Polish national army and aid the creation of a Polish state. My old unit, the 7th Uhlans, is mostly Polish, and I can speak the language passably. My father was Polish, too, though I never knew him.” As soon as he added this last, Jozef wondered if it had been too much personal detail.

Zelewski, however, met this revelation with his first genuine smile. “You know Rotmistrz Korzeniowski? Well, it’s all right, then. He’s a fine officer. And brought us some much needed remounts, I can tell you. And a Pole of sorts yourself, eh? Do you know enough to order a charge or seduce a maiden?” he asked, switching to Polish for the final question.

Jozef hesitated a moment to pick the words, but was able to deliver in a tone that passed for jocular rather than awkward, “Only if she’s as easy as your discipline.”

Zelewski laughed and slapped him on the shoulder -- confirming the easy discipline which Jozef had noted -- and said, “All right, then, half-Pole. You’ll be all right.”

A moment later the guard returned and said, “The Pulkownic will see you now.”

They found Pulkownic Gorski sitting at a table awash in papers, with several junior officers hovering nearby. Jozef saluted, stepped forward and presented his orders, then returned to attention as Gorski read them.

“A leutnant. And you’re rather young, aren’t you?” Gorski said.

“Yes, sir,” Jozef replied. Among the first lessons of the army was that if a senior officer decided to make it his hobby to pin one to a card like an unlucky butterfly, one must simply answer his questions and accept it. Having learned this lesson well, Jozef remained at attention and suffered the questioning without knowing why he was the subject of sudden ire.

“I don’t suppose you’re the son or nephew of some general?”

“No, sir.”

“Or someone highly placed in Vienna?”

“No, sir.”

“Then what damn good are you to me?”

This did not seem like a question that he was meant to answer, so Jozef remained silent.

Gorski took off his small, steel rimmed reading glasses and ran his fingers through his short-cropped, greying hair.

“Well? Have you got anything to say for yourself?” asked Gorski. “What am I to do with a pup of a liaison officer with no connections?”

Jozef looked around for help or some hint of what he was to do, but none was forthcoming. Leutnant Zelewski was directing his eyes towards an inoffensive corner of the room and avoiding the attention of Gorski.

“I was simply following the orders I was given, sir,” Jozef said at last. “My Oberst ordered me to report to you as liaison officer, and I obeyed. I am happy to do whatever is in my power to assist you, sir.”

This simple statement of fact seemed to allow the oberst’s frustration to dissipate. With a muttered imprecation he took a cigar from the box on the table before him and set about trimming it. Before he could light it, however, there was a knock at the door and an adjutant entered.

“I’m sorry, sir, there are two civilians who insist on seeing you.”

“Show them in. Show them in.” Pulkownic Gorski said. He waved Jozef and Leutnant Zelewski towards some chairs against the far war. “You’ll have to excuse me for a few minutes, gentlemen. There’s a nation to be built.”

The two young men seated themselves, and the adjutant led in two men, one with the cassock and collar of a Catholic priest, his bald head large and shiny, and the other, wearing the long black coat of a shtetl Jew, a much older man with a long white beard and a long polished homburg on his head. With bows and expressions of respect, they introduced themselves as the priest and the rabbi from Koprzywnica, about six miles to the southwest.

“The Russians still hold the village,” the priest explained, “but they are preparing to withdraw, south, across the Vistula.”

Pulkownic Gorski thanked them for this intelligence.

“No, you do not understand,” continued the priest. “We do not come to provide military intelligence. At least, not merely to provide military intelligence. We come as loyal countrymen, as Poles, but also as countrymen seeking help. The Russians have made a proclamation that all men of military age must retreat across the Volga with them, so that they cannot join the Austro-Hungarian cause. They will take from us more than three hundred men. Men with families. Men who are needed in the fields and workshops.”

“And they have demanded a special assessment from our community,” the rabbi added, speaking in Polish but with a heavy accent of some strange German variety. “Russians hate Jews.” He paused. “Maybe everyone hates Jews. But we are Polish Jews. We don’t want our money to pay for more Russian troops that take our boys and our cows and our grain.”

“We sought you out,” the priest resumed, “because you are Poles. The Hungarians and the Germans took Sandomierz. There was shooting in the streets. Looting and disorder. People were killed. I hoped that as fellow Poles you could secure our town peacefully.”

“I appreciate your patriotism,” Pulkownic Gorski replied. “And also your concerns. I will take them into consideration, but I can make no promises. My men have just fought an engagement and suffered losses. And I am responsible to the chain of command.”

“The Russians have orders to fall back,” the priest said. “It may be that all you would have to do is approach the town in force, and they would fall back without troubling our town further.”

“Father,” said the Pulkownic, standing up and gesturing towards the door. “I have the greatest respect for your wishes. But this is war. I must obey my superiors, and if I may speak so without rudeness: I cannot tell a civilian where were will or will not deploy, lest the word somehow fall into the hands of the enemy. God forbid that you and the good rabbi should be captured, but you see my difficulty.”

“Of course. Of course. I understand.” The priest bowed repeatedly. Both of men moved towards the door, but then the priest reversed course and returned, shutting the door behind him. “You must understand,” the priest said in a low voice. “They are the good sort of Jews. There are plenty of dirty Jews who hate Poles in other villages. But these are good Jews. We have a peaceful village. They cause no trouble. If you could protect them, Pulkownic, they will be very grateful. Very grateful. And if the Legion’s activities should need any financing, well, you know… Jews always have money.”

“I understand, Father,” Gorski replied firmly. The priest left.

With a gusty sigh, the Pulkownic fished a map out of the papers on his desk. Either proper military maps were not available, or they had not been issued to the Polish Legion, for this was a railway station map whose torn edged and faded colors showed it had been torn from a railroad platform and requisitioned for military use.

“Come have a look at this, little leutnant,” Gorski said to Jozef. “We’re going to see if you can do any liaising for us or not.”

The tone was not entirely friendly, but if Gorski had expected a higher ranking officer, or one with close connections to senior officers, he was no doubt still adjusting to the slap in the face he had been dealt by the Uhlans in sending an unwanted leutnant.

Jozef approached the desk and looked at the area Pulkownic Gorski indicated.

“This,” said Gorski, tapping a small back dot on the map, and the name written out next to it in Russian characters, “is Koprzywnica where our patriotic friends live in religious harmony. And this,” tapping a point just south of the town, “is the mighty Vistula, crossed by a railway bridge here. If the Russians are to pull back across the river, and take any quantity of ill gotten gains with them, or even their own heavy equipment, they must take the railroad. And if they are to take the railroad, they must cross the bridge. Now here,” another dot to the northeast of the first “is Sandomierz where your former regiment is currently stationed. And Sandomierz also has a railroad bridge across the Vistula, here. Your task is to return to Sandomierz, speak to your former regimental commander, and advise him with my compliments and all your skills as a liaison officer that if the Uhlans cross the river at Sandomierz and follow the river south, they can threaten the Russians at the bridge south of Koprzywnica. We, meanwhile, will take it upon ourselves to attack the town from the north. And depend upon it, when signals come up the telegraph wires from the bridge that they are under attack from Hungarian Uhlans, and the Russian commander sees us closing from the north, he will pack his gun and horses and whatever else he can on the train and retreat before he finds himself giving his life for the Tsar on the banks of the river. Do you understand?”

Jozef stared at the map for a moment, trying to memorize the positions of the towns and bridges, and the logic which must be conveyed to the Uhlans.

“I understand, sir, but if I may ask one question?”

“One? You’ve a very modest young man. All right. You may ask one question.”

“What reason can I give to Oberst von Bruenner as to why he should desire to threaten the Russians at the bridge rather than letting the Legion do it?”

“What, are you suggesting that the greater glory of Kaiser und König will not be enough to sway your former commander?” Pulkownic Gorski asked in a smiling tone.

Banter was a one-sided privilege. A superior might be as witty as he chose, but it was not acceptable for a junior officer to return the pleasantries.

“He may ask why he should accept my advice,” Jozef said.

“He may, he may indeed,” Gorsky conceded. “But he will not need you to tell him that there will be credit to be taken for securing the railroad bridge intact. He has a horse artillery battery attached to his regiment, which we do not, which would be ideal for threatening a railroad bridge. And he can do the thing with very little risk of his own. So the bargain which you are offering him, which von Bruenner will recognize without needing to hear you state, is that he will get the credit while I will get the town. It is an exchange which satisfies everyone. But if you try to tell him that like some clever pup of an officer, you offend him and make the task much more difficult. So just keep those wise words under that polished Uhlan’s helmet of yours. And if you can do this without making a mess of things, we shall keep you around to liaison another day.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Now be off,” Gorsky ordered.

Jozef turned towards the door.

“Oh, and one more more thing,” Gorsky added. “Take Leutnant Zelewski with you. He can keep an eye on you, and you can keep him out of trouble. So you’ll both be busy.”